AL-GHAZALI, ABU HAMID (1058-1111)

Al-Ghazali (born 1058, ?us, Iran – died Dec. 18, 1111, Tus )

also spelled Al-ghazzali, in full Abu Hamid Muhammad Ibn Muhammad Al-Tusi Al-Ghazali Muslim theologian and mystic whose great work, I?ya’ ‘ulum al-din (“The Revival of the Religious Sciences”), made ?ufism (Islamic mysticism) an acceptable part of orthodox Islam.

Al-Ghazali was born at Tus (near Meshed in eastern Iran) and was educated there, then in Jorjan, and finally at Nishapur (Neyshabur), where his teacher was al-Juwayni, who earned the title of imam al-Haramayn (the imam of the two sacred cities of Mecca and Medina). After the latter’s death in 1085, al-Ghazali was invited to go to the court of Nizam al-Mulk, the powerful vizier of the Seljuq sultans. The vizier was so impressed by al-Ghazali’s scholarship that in 1091 he appointed him chief professor in the Nizamayah college in Baghdad. While lecturing to more than 300 students, al-Ghazali was also mastering and criticizing the Neoplatonist philosophies of al-Farabi and Avicenna (Ibn Sina). He passed through a spiritual crisis that rendered him physically incapable of lecturing for a time. In November 1095 he abandoned his career and left Baghdad on the pretext of going on pilgrimage to Mecca. Making arrangements for his family, he disposed of his wealth and adopted the life of a poor Sufi, or mystic. After some time in Damascus and Jerusalem, with a visit to Mecca in November 1096, al-Ghazali settled in Tus, where Sufi disciples joined him in a virtually monastic communal life. In 1106 he was persuaded to return to teaching at the Nizamayah college at Nishapur. A consideration in this decision was that a “renewer” of the life of Islam was expected at the beginning of each century, and his friends argued that he was the “renewer” for the century beginning in September 1106. He continued lecturing in Nishapur at least until 1110, when he returned to ?us, where he died the following year.

More than 400 works are ascribed to al-Ghazali, but he probably did not write nearly so many. Frequently the same work is found with different titles in different manuscripts, but many of the numerous manuscripts have not yet been carefully examined. Several works have also been falsely ascribed to him, and others are of doubtful authenticity. At least 50 genuine works are extant.

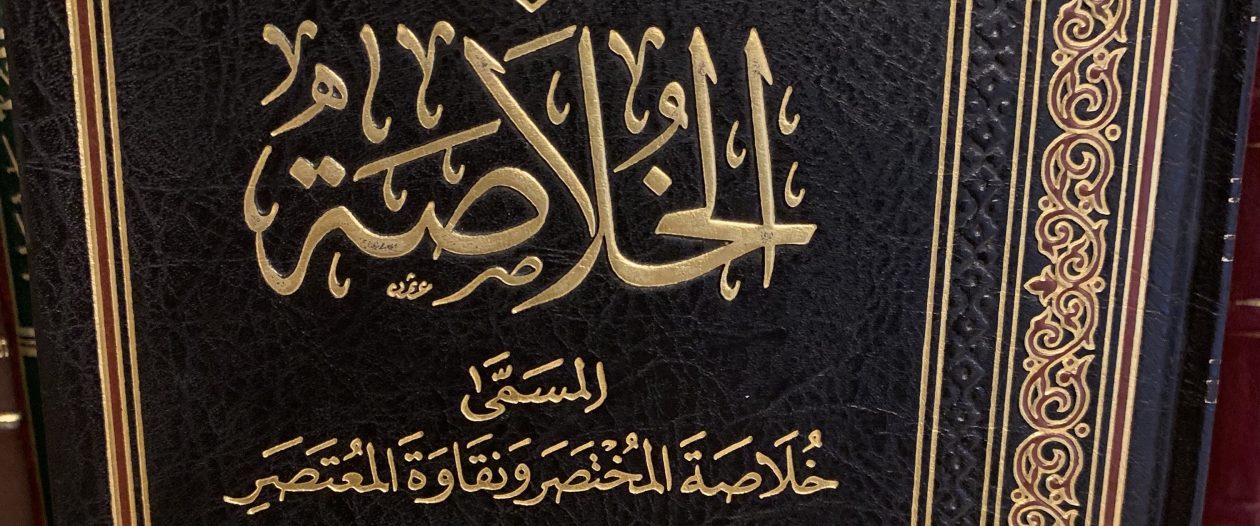

Al-Ghazali’s greatest work is I?ya’ ‘ulum al-din. In 40 “books” he explained the doctrines and practices of Islam and showed how these can be made the basis of a profound devotional life, leading to the higher stages of ?ufism, or mysticism. The relation of mystical experience to other forms of cognition is discussed in Mishkat al-anwar (The Niche for Lights). Al-Ghazali’s abandonment of his career and adoption of a mystical, monastic life is defended in the autobiographical work al-Munqidh min al-?alal (The Deliverer from Error).

His philosophical studies began with treatises on logic and culminated in the Tahafut (The Inconsistency—or Incoherence—of the Philosophers), in which he defended Islam against such philosophers as Avicenna who sought to demonstrate certain speculative views contrary to accepted Islamic teaching. In preparation for this major treatise, he published an objective account of Maqasid al-falasifah (The Aims of the Philosophers; i.e., their teachings). This book was influential in Europe and was one of the first to be translated from Arabic to Latin(12th century).

Most of his activity was in the field of jurisprudence and theology. Toward the end of his life he completed a work on general legal principles, al-Mustasfa (Choice Part, or Essentials). His compendium of standard theological doctrine (translated into Spanish), al-Iqti?ad fi al-l‘tiqad (The Just Mean in Belief ), was probably written before he became a mystic, but there is nothing in the authentic writings to show that he rejected these doctrines, even though he came to hold that theology—the rational, systematic presentation of religious truths—was inferior to mystical experience. From a similar standpoint he wrote a polemical work against the militant sect of the Assassins (Isma‘iliyah), and he also wrote (if it is authentic) a criticism of Christianity, as well as a book of Counsel for Kings (Nasihat al-muluk).

Al-Ghazali’s abandonment of a brilliant career as a professor in order to lead a kind of monastic life won him many followers and critics among his contemporaries. Western scholars have been so attracted by his account of his spiritual development that they have paid him far more attention than they have other equally important Muslim thinkers.

(William Montgomery Watt )

Additional reading:

W.M. Watt, Muslim Intellectual: A Study of al-Ghazali (1963), deals with his life and the development of his thought. Still of value is D.B. MacDonald, “The Life of al-Ghazali with Special Reference to His Religious Experience and Opinions,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 20:71–132 (1899). M. Smith, Al-Ghazali the Mystic (1944), is good for his mysticism but treats some dubious works as authentic. On this point, see W.M. Watt, “The Authenticity of the Works Attributed to al-Ghazali,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, pp. 24–45 (1952).